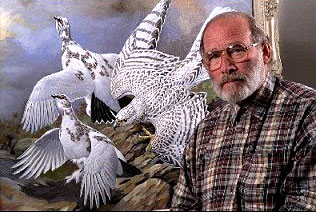

Game Birds of the World. |

|

A collection of Twelve Limoges Porcelain plates Basil Ede.

|

|

This item has been SOLD |

|

|

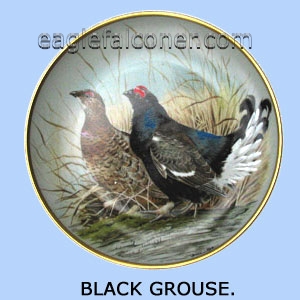

Black Grouse. |

The black grouse, which is found across the meadows and moors of Scotland, northern Europe and Siberia, is far less "black" than its name implies. While the adult male's feathering does contain a good deal of black on the breast and back, there is also a fair covering of steel-blue. The male has brown wings edged with white, and has white tail feathers. The female is not black at all, but is covered in various shades of brown ranging from reddish to greyish brown with short, dark bars. |

|

|

Capercallie. |

| The impressive capercallie is the largest of European grouse. Its name is of Gaelic origin and means "old man of the wood." This magnificent and elusive game bird has long been a favorite quarry of hunters throughout Europe. The male capercallie is predominately black with a beautiful blue-green sheen to the feathers on its breast. The wingspan of a fully grown male is often more than four feet, but the female is considerably smaller. In addittion to its size, perhaps the most distinctive feature of the male capercallie is the bird's extraordinary fan of dark tail feathers. The bird's diet consists almost entirely of vegetation. It is particularly fond of the shoots and buds of young conifers. In winter it lives almost exclusively on the needles, twigs and unopened cones of pine trees. Thus, the capercallie is much more likely to be found in regions where there are extensive coniferous forests than in prairies and other open areas where the trees have been cut down. The cock birds can be extremly aggressive. They have been known to defend their territory vigorously, atacking anyone or anything that comes near. In summer the birds usually live alone, but in winter they tend to congregate in large flocks. After mating season in April or May, the hens desert their mates to build nests, lay their eggs and raise their familes alone. The mother birds are very protective of their young, keeping watch over them for a considerable time after the chicks leave the nest. |

|

|

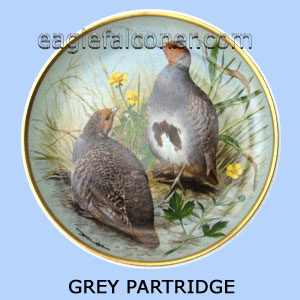

Common Partridge. |

| Perhaps more than any other word, elusive best describes the fleet and highly resourceful common partridge. Hunters the world over, from the prairie lands of North America to the forests of southeastern Europe, are all too familiar with the pertridge's quick, unexpected rush of wings when it is surprised and startled into flight. Once in flight, the partridge is capable of staging quite a display of evasive maneuvering, making this crafty bird a difficult and, therefore, highly prized trophy of the hunt. The elusive character of this bird seems even to extend itself to the matter of nomenclature, for the common partridge is frequently confused with other birds and often bears such aliases as bobwhite, quail and ruffed grouse. But by whatever name it is known, the common partridge is one of the world's most popular game birds. There are roughly 150 different varieties of partridge throughout the world, all of which share similar traits in both behaviour and appearance. The authentic partridge, ash grey and sporting a chestnut brown crescent upon its breast, is a native of Europe. Chestnut markings are also found upon its head, tail and wings. Not a particularly large bird, the partridge measures between a foot and fourteen inches in length. Partial to seeds, grain and plants for sustenance, the partridge usually builds its nest near farmlands. As many as 18 eggs are laid, and, once hatched, the young quickly display all the spirit and intelligence of their parents. |

|

|

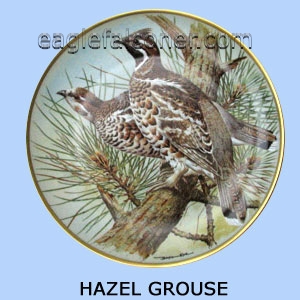

Hazel Grouse. |

| The hazel grouse (Bonasa Sylvestris ) is the only member of the grouse family to be found in Europe and Asia, where it ranges from France in the west to as far as Siberia in the East. Smaller than its North American relative the ruffed grouse, the hazel grouse is covered with brown plumage ranging from light hazel to deep, woody brown. Its feathers are heavily marked with streaks, bars and patches of black and white. The male is distinguished by a small white dot in front of and just behind each eye. The hazel grouse- unlike its American cousin - is monogamous and begins its mating season in April. After the eggs are laid, usually about ten during each nesting, the male leaves the hen and does not return until well after the eggs have been hatched. The eggs are a uniformly dark yellow with brownish spots. Covered with moss and twigs, the nest is sometimes built in the ground at the base of a tree. The bird is a creature of the forest, often being found in stands of birch, poplar, pine and aspen trees along the backs of mountain streams. The flesh of the hazel grouse, like that of other species in its genus, is sweet, light and tender, and the bird is avidly hunted by sportsmen whereever it is found. Although the hazel grouse apparently does not "drum" with its wings as does the ruffed grouse, it rises abruptly when flushed from its hiding place with the same loud whirring sound. |

|

|

Common Pheasant. |

| Mother Nature had two very practical reasons for creating the conspicuously beautiful plumage of the cock pheasant - the first, of course, being the fact that it provides a most beautiful courtship display. But equally important is the fact that the male pheasant's georgeous colouring will divert the attention of twp-legged, four-legged and winged predators away from the more protectively coloured female and chicks. The female's long tail distinguishes her from the grouse. The closely related ruffed grouse is sometimes called a pheasant in the midwestern and southern United States. Common pheasants belong to the family of gallinaceous fowl that includes the even more extravagantly adorned peacocks, as well as turkeys, grouse and barnyard chickens. Like his relatives, the pheasant is a terrestrial bird whose airbourne journeys are generally limited to escape from earthbound enemies or short flight to the branch of a tree for nighttime roosting. They are usually to be found in open country with good brush cover where they can find a plentiful supply of their preferred diet - seeds, nuts, berries and insects. The pheasants found in North America have long and distinguished ancestry, although most of the birds on the continent are hybridized varieties. Most are indigenous to Asia Minor, some having been introduced into Europe from the Black Sea area before 1056, probably by the Greeks. The Romans are believed to have brought the pheasants to England. Most pheasants found in the United States from Maine to Minnesota and south to Pennsy;vania and Kansas are a cross between the English and the ring-necked pheasant. |

|

|

Ptarmigan. |

The ptarmigan is a master of camouflage; its plumage is snow white in winter, with black eye stripe and tail, and as the snow melts it assumes a new plumage of mottled brown to match the seasonal grasses. In autumn, it moults yet again and is helped to conceal itself in its rocky grey habitat by new grey plumage. This is one of the very few wild birds known to moult three times a year. |

|

|

Common Quail. |

| Basil Ede's beautifully detailed portrayal of the common quail depicts them among the weedy grasses they often inhabit. This small game bird is generally known as a bobwhite or partridge in the southern and cedntral United States. The closely related common quail of Europe, northern and southern Africa and much of Asia has never been naturalized in the United States. The closely related bobwhite calls its own name in a pleasingly chirpy song which sounds to the farmer as though he was saying "more wet" and is regarded by the country folk as a prdiction of rain. The call is most frequently heard during spring mating season as the warm summer months are approaching. It is during this mating time that the quail's ordinarily unruffled disposition becomes beligerent. Fights occasionally break out, and the male will fiercely challenge any other birds' overtures to his selected mate. Once the pair settles down to nest building, the male becomes a devoted husband and father. If some harm should befall the femal, he may even complete responsibilty for feeding and protecting the chicks. The birds are not strictly monogamous, however, since once in a great while two females may occupy the same nest in a ménage á trois. The incubation period for the eggs is approximately twenty four days, and shortly after they have broken from the egg they are ready to leave the nest. When they are still quite small they desert the nest completely, traveling in a small covey through the bushy fields and pastures in search of food. |

|

|

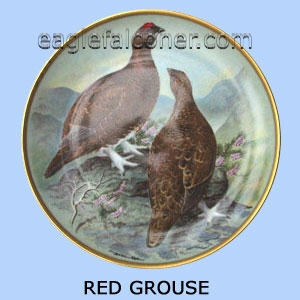

Red Grouse. |

The red grouse can truly be called "a subject of Great Britain" for it makes its home in various parts of England, Wales, Ireland and on the moors of the Scottish highlands. Because it can fly for short distances with great bursts of speed, the red grouse is a favourite, and very challenging,game bird for sportsman, and many are bagged in Scotland each year during the late summer shooting season. |

|

|

Red Legged Partridge. |

| The red legged partridge is among the most challenging and difficult-to-bag of all game birds. This canny bird, distinguished by its red legs, black eye stripe, and by the clear brown and black stripes on its wings, seems to know every trick to baffle and confuse an inexperienced hunter. Like other members of the partridge family, it takes off in an instant when it is startled and darts away so quickly that it is out of range in no time. It will frequently take to the air behind a tree trunk or a thick bush and is often several feet off the ground before a hunter is even conscious of its presence. And occasionally it will circle around behind a hunter to escape being detected. The female instinctively builds her nest in a location unknown to the male, for he will disrupt the nest if he finds it. She lays up to eighteen olive-green eggs, which hatch after being incubated for twenty four days. During this time, the female is ever on the alert for predators. She will flee from the nest to distract an intruder and lead it away or will fight to the death if necessary to defend her brood. Immediately after they hatch, the chicks are ready to fend for themselves, but for some time the female remains with them and will shelter them under her wings at night. Soon the young birds learn to fly short distances. Then they are able to begin roosting in trees, and it isn't long before they can fend for themselves. A native of Europe, the red legged partridge ranks on a level with the grey or Hungarian partridge and the chukkar partridge as one of the world's most sought after game birds. |

|

|

Chinese Ring-Necked Pheasant. |

| The Chinese ring -necked pheasant is probably the most widespread and best known wild fowl in the world. Originally it was a native of northern China, but the pheasant's desirability as a game bird and its ability to adapt to new environments led eventually to its distribution throughout the world. The ornamental plumage of the male makes it one of the showiest birds in avian kingdom. It has an iridescent green head, red face patch, white neck ring, reddish-brown upper parts, golden flanks and greyish wings. In contrast, the smaller female has mottled buffy brown feathers and lacks a neck-ring. Handsome hearty birds, pheasants have compact round wings that propel them through the air with short rapid beats. Despite their ability to fly, however, they prefer to run away from intruders, flying only if it is necessary. Ring-necked pheasants are gallinaceous fowls like their distant cousins the domestic chickens. They will eat almost anything their powerful claws scratch up from the ground including berries, seeds, nuts and insects. The males establish harems during the breeding season, attracting females by extending their wings to show off their beautiful plumage. But once the eggs are laid, the males fly off, and the female becomes solely responsible for her brood. Although the ring-neck is a popular quarry for hunters the world over, protective laws have helped preserve the species. In most places it is illegal to hunt females, and their are usually more than enough male pheasants to ensure a thriving population. |

|

|

Common Snipe. |

| The long-billed, brown feathered birds depicted among snowy marsh grssses by renowned nature artist Basil Ede are shorebirds of the sandpiper family. Native to both the Old and New Worlds, the common snipe and its relative, the American woodcock, are the only members of their family that may legally be hunted in the United States. The snipe's slender pointed bill is particularly well-suited for searching out earthworms, one of its favourite foods. It also eats aquatic insect larvae, snails and small crustaceans. Although the common snipe searches out its food during the daylight hours, long journeys are made under cover of darkness. The courtship display of the male bird is a unique performance. Circling and twisting high in the air, it will suddenly set its wings, spread its tail feathers and swoop toward the ground. The rush of air through the stiff tail feathers produces a pulstaing, whistling sound which may be regarded as the mating call of the common snipe. It is generally a solitary nester, inhabiting swamps and marshy meadowlands in the more northern latitudes, often migrating southward as far as South America and Africa in the wintertime. Those who winter in the north remain close to flowing streams or springs which do not freeze solidly. The grass-lined nest contains four slightly pear shaped eggs of a yellowish olive, spotted with darker brown. The brown-shaded feathers of the young are excellent protective colouration, while the older birds have more distinctive markings of brown and buff stripes, their white under-feathers streaked with brown. |

|

|

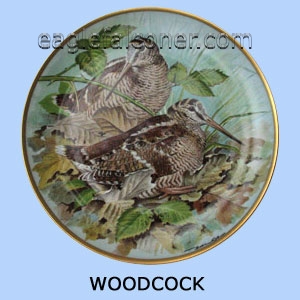

Woodcock. |

| The woodcock is probably the most adaptable of all game birds. Its colours blend perfectly with the swamp or woodland it inhabits, and because of its habits and colouring it is not easily threatened by man. Basically cinnamon brown with black stripes on the back of its head and a black and grey variegated pattern over its back and wings, the woodcock is not easily detected in the wild. If its nest is disturbed, this bird will carefully pick up its young between its thighs and carry them, one at a time, to a safer place. The woodcock is so determined to safeguard its young that it may make many trips back and forth until all its chicks are placed in a new shelter. While this action has been observed many times, ornithologists have also seen an even more amazing phenomenon - woodcocks flying with their young on their backs. Since it is virtually impossible for the mother to place her young there herself, it is believed that, like chicks and ducklings, the woodcock young climb onto their mother's back as she sits on the nest. When she si surprised and flies off, the young clutch her feathers and find themselves airborne, too. With its explosive way of emerging from its hiding place and streaking through the air, this game bird is an exciting and challenging target for hunters. Since it is so secretive, dogs are sometimes used to locate and flush it from hiding. However, federal regulations have set limits on the numbers of woodcock a hunter can bag in one day, and this has served to protect and help preserve this quick, darting night flier. |

|